Presenting DARK BREAKERS: video and interview with C. S. E. Cooney + launch sale

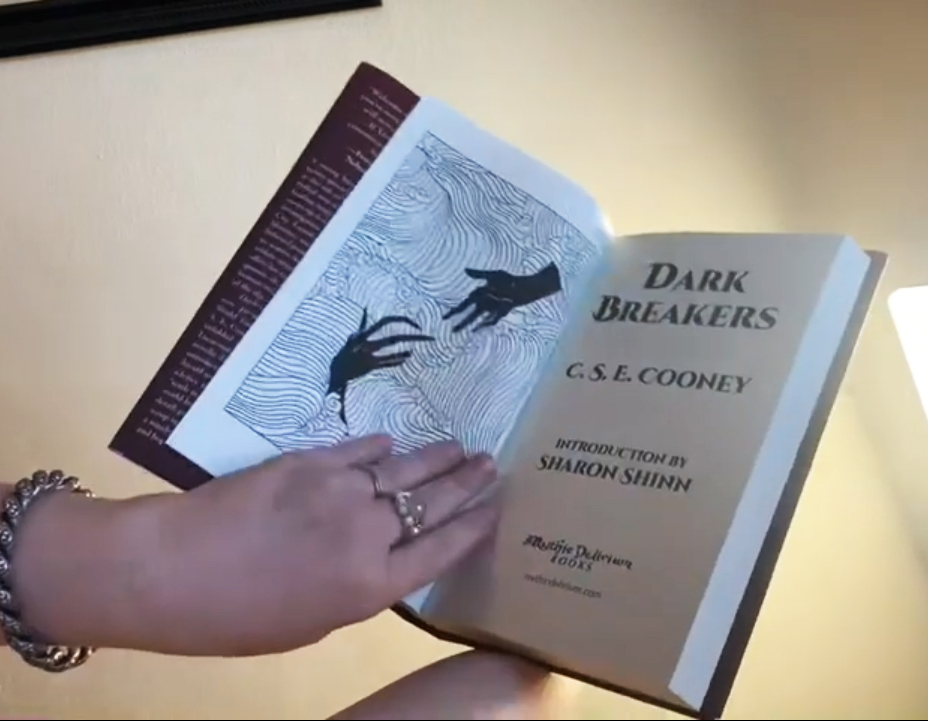

Mike Allen / Tuesday, February 15th, 2022 / No Comments »Today the special pre-order sale that we have been holding on e-book editions of C.S.E. Cooney’s new collection Dark Breakers officially switches to being the launch sale for the book, as as of today Dark Breakers is officially out in the world and available. The discounting of the e-book price from $6.99 to $2.99 will continue through the end of the month.

We’re pleased also to have added our longtime partners in business, independent e-bookseller Weightless Books, to the list of platforms carrying Dark Breakers. Weightless, too, is participating in the discount launch sale.

Here are links where you can get those discounted e-books:

Ebook: Amazon | Amazon UK | Amazon CA | Amazon FR | Amazon DE

Amazon AU | Nook | iBooks | Kobo | Google Play | Weightless

And for the trade paperback and hardcover editions, all the links you could possibly need are here.

To celebrate the dawn of Dark Breakers, we have a couple of fun things to share with you. First, here is the “unboxing video” that author C. S. E. (Claire) Cooney recorded earlier this year when she finally got to open her boxes of contributor copies:

Second, we have a deep-diving interview with Cooney about how Dark Breakers came to be and what makes its three worlds tick, or click, conducted by our new-ish assistant editor, Sydney Macias, who has been working with us behind the scenes since Spring 2021 and at last makes her “debut” on our site with this delightful feature. Read on!

SYDNEY: How would you characterize Dark Breakers — is it a collection, a mosaic novel, both, something else? Other works of yours have sometimes blurred the distinction between short fiction and novel, how would you categorize your previous books?

CLAIRE: I think Dark Breakers falls under “collection” in a shared world. I discovered Charles de Lint’s books as a teenager, and I loved to read his short stories, novels, and novellas that all seemed to connect to each other. Characters in one story would have a friend, barely mentioned in passing, who’d end up being the protagonist of a whole other book! It was a way to build a world (or even just a single city) over time. I connected to an entire community that never existed outside the bounds of his pages.

This was different from a series of novels with a set protagonist, whom you get to know deeply over time, and watch how one person, or even a group of people, change over an arc of years. I loved series like this too, but wanted to play with a more weblike network of shared-world stories written over a span of years, changing as a city changes, as a community changes (and as I, the writer, change).

Categories of fiction—short stories, novelette, novel—are mostly only useful for magazine guidelines and award requirements. Sometimes I’ve set out to write a novella that ended up being a short novel—indeed, almost too short for a proper novel! It was a novella in everything but length! It was a novella in intention.

This has happened, I think, twice by accident. Many times a short story has ended up needing a lot longer than the word limit I was trying to hit with it. The novum, perhaps, was too ambitious for the length, or perhaps there were too many characters to handle in too few pages. It’s hard to say.

I could say “the story wants this” or “the story demands that,” but that sort of thinking is next to useless when it comes to selling a story to a given magazine or anthology. Writing a story is one thing. Writing a story for other people to read (hopefully, potentially) is another. That requires a little more discipline as far as word limits, genres, and even sometimes themes go. If a writer is going the route of publishing in magazines and anthologies, and submitting their materials afterwards for awards, they will definitely be highly motivated to stay within certain word limits and genre lines for the sake of eligibility.

SYDNEY: What genre tags might you apply to this collection?

CLAIRE: Well, let’s see here.

For the collection as a whole, probably: #fairyfiction, #gildedagefantasy, #fantasy, #darkfantasy, #portalworldfantasy (to an extent), #secondaryworldfantasy, #urbanfantasy (not our world, not present time, but definitely set in a city, mostly), in some cases #fantasyofmanners, and since I really love the sound of it: #hopepunk

I was looking at popular romance and fantasy tropes that some writers use for hashtags on Instagram and in the FanFic community, and tried my hand at breaking down Dark Breakers a bit that way.

I’m actually not sure how useful this is, but categorization is always fun, or at least kind of hypnotic. Well, for me anyway. I find it relaxing to alphabetize books and organize my jewelry boxes, so…

For “The Breaker Queen”: #forbiddenlove, #alienhero (for “alien” read “gentry”), #fishoutofwater (this is on a world-to-world scale rather than small town to big city, but I still think it stays), #hiddenidentity, #shapeshifters, #richestorags, #royalty, and in a stretch #secretbillionaire (if you want to count a Gentry Queen disguised as a human maid a secret billionaire).

For “Two Paupers”: #enemiestolovers, #sharedpast, #quest, #cursed, and to go with that (a bit cringingly) #beautyandthebeast (Gideon’s a real beast—of the “jackass” variety—and I love him and all, but he’s a big problem. But sometimes people change for the better).

For “Salissay’s Laundries”: maybe #ghost (for a given definition of “ghost,” even by gentry standards), #partnersinfightingcrime, #grimdarkfantasy, and #socialjusticefantasy—in the style of its soul-sister novella Desdemona and the Deep.

For “Longergreen”: #lovetriangle, #grievinglover, #secondchanceatlove, or maybe #soulmates. Plus, there’s a definite #maytodecember vibe going on, except it’s complicated because immortals vs mortals. You can have an older mortal and a younger immortal, but someday that’s going to change, and the mortal becomes dust, right, and the immortal keeps going on.

For “Susurra to the Moon”: #comicfantasy, maybe, (sort of?) #sciencefantasy—since the story mainly has to do with two gentry queens wanting to go the mortal moon, but also having to deal with little things like human space agencies. It’s really just a #lark, if you know what I mean.

SYDNEY: Why did you choose the Gilded Age as a backdrop for this collection?

CLAIRE: There was a reason I initially chose that era when I first began “The Breaker Queen” and “The Two Paupers”, but then there was a reason I stuck with it. This was a project that spanned several years. I wrote the first two novellas before I wrote the last three stories, and between, I wrote Desdemona and the Deep: a standalone novella in this world, not found in Dark Breakers. Therefore, in “Salissay’s Laundries”, the first story in this world I wrote after Desdemona, I found myself leaning in and going a bit darker and more political, matching Desdemona’s tone and intent.

When I moved to Rhode Island in 2011, I spent some time going on a few day trips, visiting forests and beaches and the towns surrounding my little town. It was Sharon Shinn who advised me to visit The Breakers in Newport. The mansion was everything a lady with a life-long love of glittery, golden things could want: appallingly lavish, extravagant, and deliberate. The thought and care and pride that were poured into the architecture and art, not to mention the grounds themselves, were mind-bending. Every block of marble and platinum panel and renaissance-style painting had its reason and its place. The whole thing was almost oppressively impressive—as it was built to be. That the Breakers was considered a “summer cottage” by the Vanderbilts who lived there almost made me guffaw. For the rest of us peasants, it was a palace.

My first thought when thinking about setting a story there was that the main character might be some serving maid who worked there by day for the humans, but by night, walked through the walls into another Breakers entirely, where she ruled as queen. Every serving maid’s fantasy, right?

For a while, I tried to set my story in the actual Breakers, but historical fiction requires so much research if you want to get it right. I was also uncomfortable knowing there might still be living relatives of the historical figures I would be writing about. It felt… confining. So I branched out into what I liked best: secondary world fantasy. I love world-building! Such liberties I could take! But I wanted to use so much of what I was learning about the Gilded Age, all these delicious details, all this sumptuous stuff. I wanted the vocabulary.

And then, of course, the older I got, and the more research I did into that fin-de-siècle era, the more I started seeing parallels between that age and ours, the great disparity of rich and poor, the swift innovations in industry, the high cost in lives and resources, the growing agitation for women’s rights, workers’ rights, civil rights. That’s when it became less of a pretty setting for a fantasy story and an opportunity to use this secondary world as a canvas upon which I could re-imagine my own.

SYDNEY: What were your sources of inspiration for the Valwode?

CLAIRE: So, have you ever seen the movie Legend? There’s this wood, and it just kind of… twinkles. The light is just so. There are little things that seem to skitter and watch from the corner of the screen. There are monsters in the bogs (Meg Mucklebones forever), and trickster pixies, and—of course—the Gump. You randomly run into unicorns at the stream beds. And this reminds me of the forest in the The Last Unicorn, that the title character keeps sweet as spring by her very presence.

There are so many forests in fantasy and science fantasy, but my first visceral, visual influence were probably 80’s fantasy films: from Willow where the death dogs hunt you, to Labyrinth where the Fireys leap out at Sarah and dance for her, taking off their heads off and throwing them at each other—then insisting she do the same. There’s a wood in the one (or several) of the Ewok adventures, with, I think a Witch Queen who turns into a raven, and Krull, with a teleporting Black Forest full of outlaws who are occasionally infiltrated by changelings. Plus, all those fairy tales full of forests, where the protagonist often ends up.

I named the Valwode to marry the words “veil/vale” and “wood.” There’s some wordplay with “veil/vale,” as in “piercing the veil” to see into another world, and “vale” as in “the Valley of the Shadow of Death,” and “vale” as in the Latin for farewell. I can’t remember if it was Neil Gaiman or Terri Windling writing that Faerieland and the Land of Death share marchlands, but I always liked that idea. There are different version of fairytales that have fairies stealing people away, or Death stealing people away, or sometimes the Devil stealing people away: the stories are similar, as are the bargains those left behind make to get their lost love ones back. So that’s something I think about when I play with the gentry of the Valwode, and the Valwode itself: beautiful, deadly creatures in a beautiful, deadly place, where “immortality” and “death” might as well be synonyms.

SYDNEY: There’s a lot of art making in the book: painting, sculpting, writing. Why did you choose art as such a strong tie into this world of magic?

CLAIRE: Probably there’s some compensatory writing happening there. When I started The Breaker Queen, I was living below the poverty line, working a $10/hour job part time, and getting food regularly from the food bank. I was living in an attic apartment with my mother in Rhode Island. We didn’t have much, and every single bill was stressful. And yet, I was deliriously happy. I finally had time to write. I was living in a new town, in a new state—one I’d always wanted to live in—and while I didn’t have any money, what I had oodles of was time. Time to write! At last!

So often the lot of artists is to be very poor, to do one’s art in one’s spare time, while trying to scrape together a living the rest of the time. Historically, some artists had (or even have, present tense, with such virtual platforms as Patreon) patrons to help them make ends meet while they make art. One story artists sometimes tell themselves is that artists are special, somehow more wise and insightful than your average (choose a color)-collared workaholic, that they can see further, feel more, recognize patterns and therefore transcend them, offer something invaluable and necessary to society’s survival with their work, etc.

It’s a good story, especially when you’re debating whether to pay your electricity bill or your college debt installment that month. It helps one go on.

I don’t think that artists are actually any better than anyone else on any given day. Generalizing by group is rarely a good idea. But it was fun, and a relief in those early days, to give my artists the gift of the Valwode: just for being themselves, utterly themselves. Though impoverished, each character’s connection to their art (both innate and learned) gave them the ability to not only transcend class, but whole worlds, and also granted them protection where otherwise they might vulnerable.

Later, in “Salissay’s Laundries”, after a certain four-year presidential term was over, I guess I wanted to give journalists that same protection. And after several friends, and friends of friends, and family of friends died in late 2019 and throughout 2020, I wanted to give a gift of possible immortality and infinite love to the elderly.

And then, in “Susurra to the Moon”, goddamnit, I just wanted to have some fun.

SYDNEY: There are some really compelling couples in the book. What were you most excited to explore for these different relationship dynamics?

CLAIRE: Again, I wrote the first two novellas quite a while ago, and was strongly influenced already by my incessant love of the romance genre, both romcom and romantic fantasies. I wasn’t as aware of romantics tropes as I am now, and maybe would have done some things different (i.e., Gideon and Analise in “Two Paupers”).

Gideon and Analise are some of my favorite characters, and long before any of the Dark Breakers stuff had even been conceived, I’d written them a one-act play that, years later, became the basis for their backstory. They’ve always fascinated me, and the more I grew up, the more I wanted to do right by them.

It’s so seductive to slip into certain tropes, and “the male jackass with the heart of gold and the female who redeems him” was so much under my skin that I never questioned it. In my most recent revision and expansion of “Two Paupers” for this collection, I was go glad to dive in with my eyes a little more open, a little more aware of tropes and habit, and question them, pry them open a bit.

Since writing “Two Paupers,” I also, you know, fell in love and got married, which helped. It helped even more that my husband is an award-winning SFF writer himself and an English professor, and when he sees a character behaving in a way that makes him squick (especially a male character, who’s supposed to be lovable by the end and not a toxic, radioactive mess you want to bury in a cave beneath the desert), he’ll tell me so. In no uncertain terms.

I really like the relationship in “The Breaker Queen”, because it takes the hot immortal thing (like every male vampire and female human lover ever) and flips it. I also like riches-to-rags story, where the end goal isn’t more money and power, but a life well lived, and even an awareness of death that makes life sweeter, dearer, more intentional. It also allowed me to recreate the “blonde, buxom, dairy-maid type” in a male image—and not only that, but in Elliot’s image: someone wise, insightful, slow to judge, and loyal.

I loved revisited the character of Salissay in “Salissay’s Laundries.” She has a cameo in Desdemona and the Deep, and I always wanted to know more about her. I like to think of her as a queer, uncanny Nellie Bly. While this story is not a romance, I liked to pair up a sort atheist journalist who doesn’t believe in gentry with the gentriest of gentry, and see what happens.

In “Susurra to the Moon”, I loved to take two characters who, all the way back in “The Breaker Queen”, had nothing to do with each other, and over time and several stories (including Desdemona and the Deep), have ended up completely transformed and in love with each other. I had so much fun showing them off in a domestic situation, long after (by human standards) their love story originated. What is 60 years of married to a gentry, after all? What do immortal gentry hanker after? Mortal things, of courses. Like the moon.

SYDNEY: What are you working on next?

CLAIRE: I am working on a book called Fiddle, which actually takes place—again!—in this same world of Dark Breakers and Desdemona and the Deep. It is a wild, rompy, rom-com-y goblinpalooza, and it makes me laugh out loud even to write it. There are goblins, demons, gentry-babes, Fathom Folk, all sorts, and they all get into such a mess. There’s also a spaceship, and prophecies, and a that-world-equivalent of our own 1980’s, so it’s hysterically fun to research. Right now it’s kind of wild, and I’m reluctant to tame it, but eventually the plot will heel at my command, even if, at present, it’s a bit of a wolf pup.

Sydney Macias (Assistant Editor, Mythic Delirium Books) is a practicing novel writer whose interests take form in metaphysical settings. She is working toward a Bachelor of Fine Arts with an Emphasis in Writing from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Follow her on Instagram at @_syd.mac_.